Law enforcement agencies are always testing out new technologies in the hope of reducing costs and making their jobs easier. This week we’re looking at three that deal with aspects of surveillance, drug-dealing, and responding to people who keep changing their stories.

Police Testing GPS Tracking “Bullets”

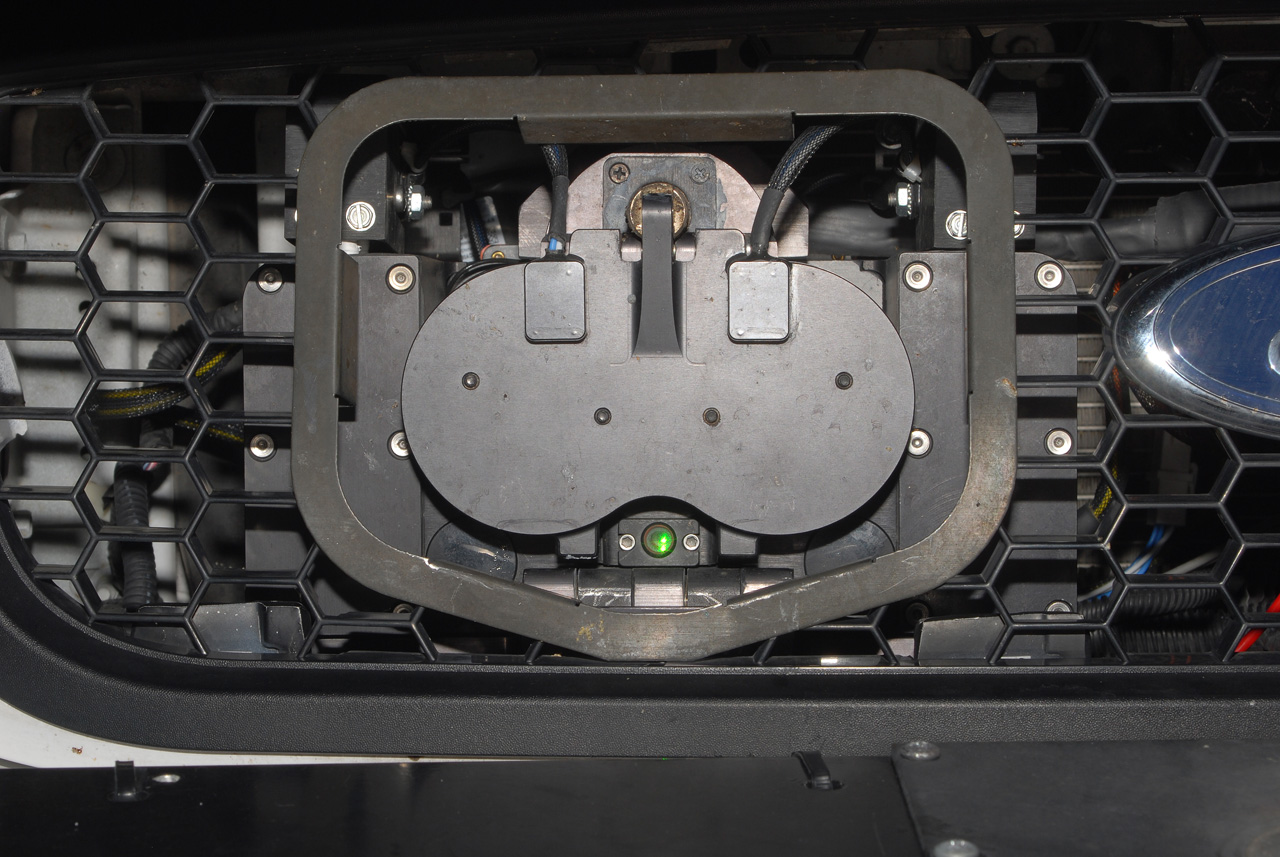

It’s a contraption you’d expect to see in a James Bond movie; a laser-guided, double-barreled cannon hidden within the front grill of a police car. When activated, it stealthily launches a sticky pellet at the vehicle in front, splatting it with a gooey mass that carries a GPS tracking device.

The idea is to allow officers to back away from high-speed pursuits, to give them the confidence of following a suspect even if they travel out of sight. The GPS data can be tracked using a computer or cellphone and shared amongst other patrol cars for a more coordinated response. The hope is that by taking the feeling of pursuit away from fleeing suspects, they’ll avoid the high speeds that too often result in property damage or death.

Manufacturer StarChase has been developing the technology for several years now and seem to have all the angles worked out. A laser helps officers know when they are within the needed range, emitting an audible beep when it’s found its target and then rapidly beeping when the police are close enough to shoot (within a few car lengths). The cannon uses pressurized air, strong enough to fire pellets accurately, but without an explosion or loud bang that would give away its use and the gooey mass that surrounds the GPS pellet is so thick that it avoids doing any damage to the pursuing car.

State Troopers in Iowa recently used the system to tag a truck that was driving erratically across the front yards of several houses. Left to think he’d gotten away, the driver made a stop to pick up an acquaintance only to find himself suddenly surrounded by police who had been tracking him from afar the whole time.

Police in St. Petersburg, Florida are giving the GPS cannons a six month trial and if they’re happy with them will deploy them at a cost of $5,000 for each police car outfitted and $500 each for each GPS pellet used.

Officer Google Glass

Whether it’s cameras mounted inside police vehicles or bystanders using their cellphones to capture the action, video footage has proven invaluable to law enforcement, motivating agencies around the world to give their officers cameras they can wear.

One of the cameras used by UK police, the RS3-SX by Reveal Media

A number of companies, from Panasonic to Taser International, are marketing Body-Worn Video (BMV) systems of different sizes and use. In the United Kingdom, police have just equipped 450 officers in Hampshire with wearable cameras and 530 officers in Staffordshire, following similar rollouts in Germany, Sweden, France, and the United States. Here in Canada the cameras have been tested by police in Edmonton, Calgary, Victoria, Ottawa, and Amherstburg, Ontario.

In most cases the cameras are worn with a vest, capturing the action at chest height. Police have complained that this offers a view of where an officer is facing, but not where he/she may be looking. Far too often what is usable is the audio, not the footage, so to step things up one manufacturer, CopTrax, has connected their system with Google Glass, a wearable computer that places a camera just above the right eye. It records everything the officer sees, makes it clear where he/she is looking, what gestures others are making towards them, and can even follow where the officer is aiming should they draw their weapon.

This past September, Sergeant Eric Ferris recorded the first arrest using Google Glass in Byron, Georgia. He pulled over a parole violator who was speeding and as you can see in the clip below, the camera recorded everything from his perspective. The hope of law enforcement agencies is that such footage will lead to quicker resolutions over charge disputes and that the presence of a camera might make people think before they act out. Since outfitting vest-worn cameras to their officers, police in Rialto, California say they’ve seen force being used against their officers go down by 59%.

Of course it isn’t just the citizens who can get carried away and so the American Civil Liberties Union has responded to the technology with recommendations that it be designed so that officers cannot edit the footage and that the resulting video be made available to both lawyers and defendants, with unused footage deleted after 30 days to maintain standards for privacy.

CopTrax says the Google Glass camera can be set to record the moment an officer turns on the sirens or drives at a certain speed. It can upload its footage automatically to a secure server and stream it live online for supervisors to monitor.

City Sewers Know Where All The Meth Labs Are

It’s unavoidable. If you create home-made explosives or cook a batch of illegal drugs, you’re going to release fumes and chemicals into the environment. Even if you avoid pouring chemicals down the drain, the fumes will find their way to surrounding plants and trees and seep into the soil. When investigators tracked the source of explosives used in the 2005 London bombings to a house, a telltale sign was the death of all the garden plants in the backyard.

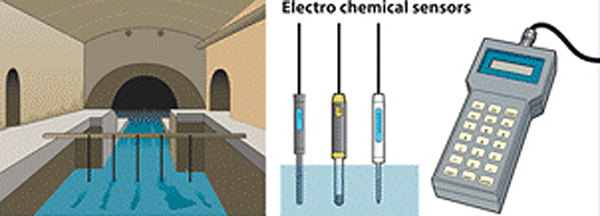

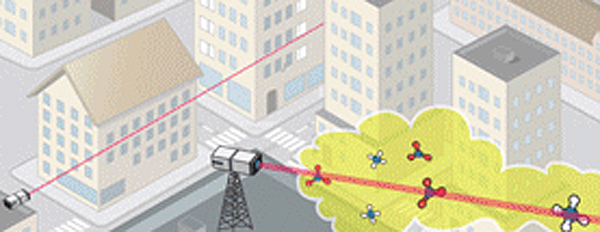

A European Union-funded research project called Emphasis is exploring the idea of creating a city-wide network of sensors to detect such fumes. Led by analytical chemist Hans Önnerud, the proposed system begins first with rooftop sensors that can filter through air currents for chemical traces and then is backed by sensors placed throughout the sewer system, testing for liquid traces amongst the flow.

When either system raises the alarm, undercover investigators can then be sent out to the general area to pick up the scent using portable air scanners that can then narrow it down to a specific building.

So far Önnerud and his team have demonstrated that the idea works in a lab, but will need to prove that their sensors can stand-up to the toxic flow of a sewer system. It’s a feasible enough of an idea to inspire several other research teams, including the Fraunhofer Institute in Germany, to develop their own versions that can focus on drug detection or even help utilities detect problems in the sewer system such as blockages before they develop.