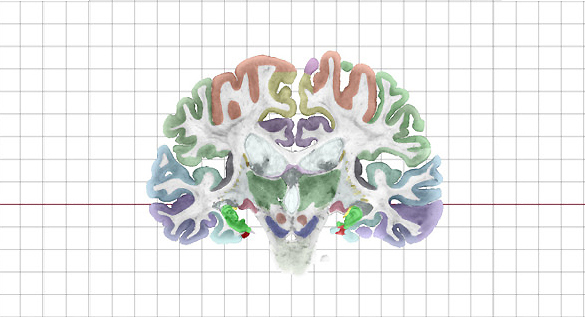

For the first time researchers have scanned a human brain at the cellular level, revealing an unprecedented amount of detail and structure on the most mysterious part of our bodies. When you view the brain at this level of magnification it becomes as expansive as the universe, and so rather fittingly, Dr. Jacopo Annese and his team at the University of California, San Diego, have used the software behind Google Maps to organize their imagery into an online atlas.

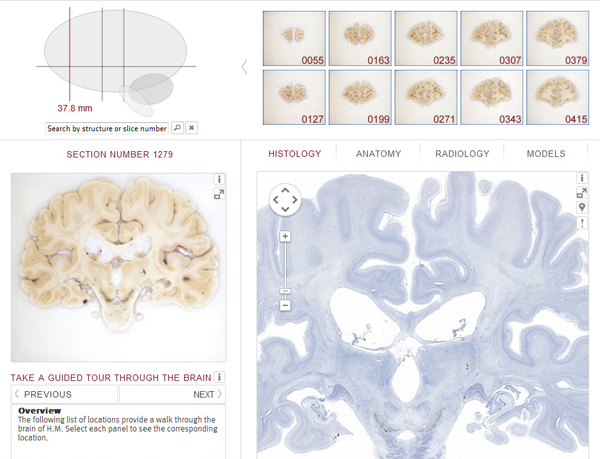

Remember the first time you saw Google Maps, how revolutionary it was? The HM Brain Atlas delivers the same astonishing change. We’re going from a “map” of the brain that’s as primitive as a colouring book to actual photographs that begin with a view of the brain in its entirety that can then zoom down into the “rooftops and mountains” of the mind, then further down to the major “highways and city blocks”, and then again down to the “bike paths and hidden alleyways” where, just as you can see the front door to your house on Google maps, you can see the very fibers within the Hippocampus, each just a few microns wide.

“These are the fibers where the memory of our first kiss travels” explains Dr. Annese, “where memories are created, where we perceive beauty.”

As with Google Maps, everything is labelled and you can view sections in both 2D and 3D views. Researchers can access it through a web browser from anywhere in the world and interactive tours can be taken through areas of interest. When doctors see areas of concern in their patient’s MRI or CT scans, they can reference the HM Brain Atlas to better understand what the structure of that area looks like and how it may be damaged.

The atlas was created by slicing a donor brain into 2,401 slices, each as thin as a human hair. Each slice was photographed by a 90,000 Megapixel microscope into 60,000 high-resolution photographs that are so large that if you were to print one off you could wrap the exterior of a building with it. Combined, the imagery takes up one Petabyte of information, the equivalent of 1 Billion eBooks or 3,000 years of MP3 music.

Although free, researchers are required to register for access to the atlas. You can skip this step and simply explore a small sample of the atlas here as well a demo of it’s workings here.

The HM Brain Atlas gives us a map of the brain’s connectivity and the hope is that by delivering a clear view of its structure we can better understand neurological diseases, but also learn more about how we dream, think, and record our lives. For now the atlas contains the imagery of a single brain, that of donor Henry Molaison, but over time more donors represtning a range of different conditions will have their brains scanned into the project and the atlas will continue to grow.

The World’s Most Famous Amnesiac

The HM Brain Atlas is named after Henry Molaison, who left his brain to the project when he died in 2008. As the world’s most famous amnesiac, a man considered to be the most important neurological case in medical history, his story is as fascinating as the atlas itself.

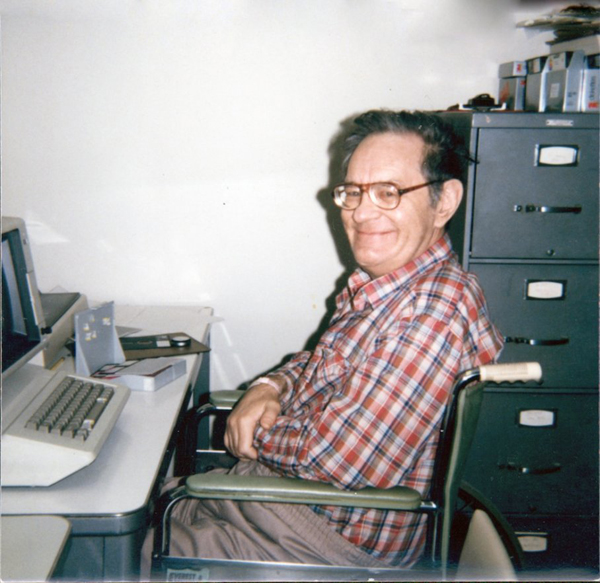

Henry at his computer. Photograph by Allen Lane

From childhood Henry coped with severe seizures that became ever more debilitating as an adult. In 1953 he agreed to an experimental surgery to try to stop them, and while it worked in controlling his epilepsy, it also left him incapable of forming new long-term memories.

Henry could remember the people and events of his life before 1953, but from minute to minute moving forward everything new simply vanished. He couldn’t tell you anything about his day or what he had for lunch and every new person he met was a stranger for life. In conversation he often repeated himself.

You might think that would make him an irritating person to be around, but by all accounts he was a sweet, intelligent man who treated everyone as a friend.

He used his intelligence where his memory failed him, working out that he had a problem remembering things, that it was no longer 1953, and that the people around him were familiar even if he didn’t know them. He described Suzanne Corkin, a Professor of Behavioural Neuroscience who worked with him for 46 years, as someone he must have gone to High School with.

“He was a pleasant, engaging, docile man with a keen sense of humor” writes Corkin in her book Permanent Present Tense, “who knew that he had a poor memory and accepted his fate.”

As a detective solving his own puzzling life, Henry understood the importance of his wits. He did crossword puzzles to try to keep them sharp. He worked out that he was no longer being treated for epilepsy, that the operation must have happened, and that the research he was cooperating in was for something new and greatly beneficial to others. This allowed him to avoid being merely an object of study and instead become an active participant in the research being done on him. He said he had thought about being a doctor in his youth, so the work made him very happy.

His unique case drew global attention and for protection his identity was kept hidden. In medical journals he was simply referred to by the initials “H.M”. That he couldn’t learn new facts, but was able to pick up new skills was intriguing to scientists everywhere, but only a few were allowed access.

In his lifetime the research he participated in lead to the discovery that the hippocampus played a key role in the forming of long-term memories, that intelligence isn’t reliant on memory and that memory is processed by special circuits within the temporal lobe. His condition proved that there are different memory systems addressing different functions.

Professor Corkin recorded a conversation with Henry in 1992, asking him how he felt about his difficulty remembering things.

“Well, I don’t feel good about it” he replied, “but I think what is found out about me will help the medical people scan other people too and help them.”

Henry Gustav Molaison 1926 – 2008

His full identity was released after his death to acknowledge his role in discoveries that have significantly improved the lives of millions of people. With the support of his family and guardians he gave permission for his brain to be used by Dr. Annese and his team who have just published a paper on their findings during the process in the journal Nature here. The HM Brain Atlas now exists as a tribute to the person he was as well as a way of continuing his legacy.