For longer than anyone can remember, public exhibitions have been used to gather large crowds to test out new ideas that unite the worlds of art and science together. This week we’re exploring three extraordinary examples that are sure to surprise you.

Stranger Visions

A wad of gum on the sidewalk, a cigarette butt on the patio, or even a hair left on the sink of a public bathroom, you’d be amazed at just how much personal biological information you cast about as you move about from place to place. New York-based artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg was curious as to just how easy it would be for someone to collect that information. After taking a quick crash course in collecting DNA samples and downloading some free software she was amazed to find it a very easy and inexpensive thing to do.

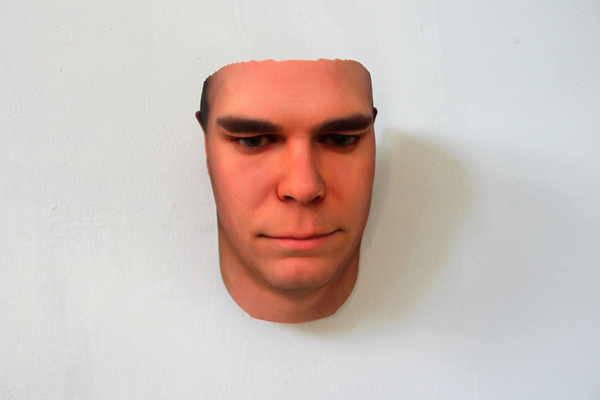

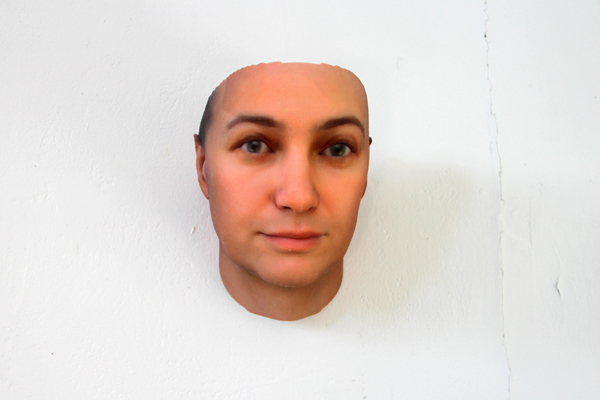

From a fresh sample found on the street, Dewey-Hagborg’s process can pick out fifty character traits, everything from gender and eye colour to susceptibility for obesity or the size of the person’s nose. It isn’t enough to identify a person, yet, but there’s more than enough descriptive features to assemble a vague picture of the person and enough that she’s used a 3D printer to manufacture a series of facial sculptures made from actual samples and based on real people.

She displays these faces publicly as an art exhibit called Stranger Visions and while it’s quite possible that someone may step into her gallery and unwittingly come face-to-face with themselves, it’s unlikely they’re recognize what they see. Even a sculpture she’s made based on her own discarded DNA has but a passing resemblance. In time she thinks she’ll create closer matches as she learns to process DNA samples better, but doesn’t expect to ever be able to identify strangers, instead she thinks it’s important to note just how easy it is for an amateur to collect this personal information and that the quantity is enough that someone will find a use for it in the future. Best we think this through before they do.

Scopify ROM

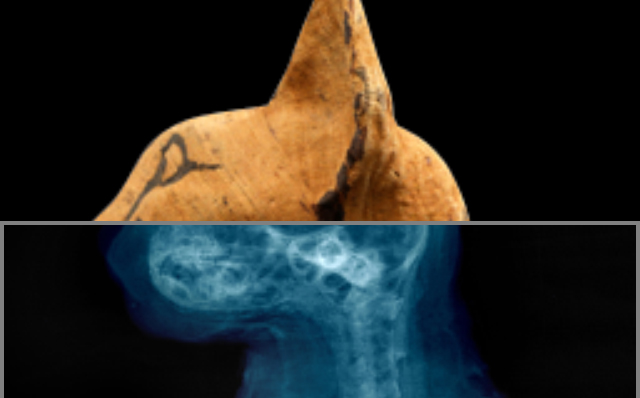

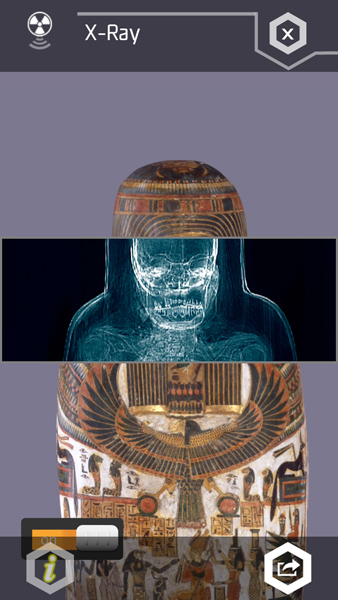

With many museum artifacts it’s a case of look, but don’t touch. A new app launched at the Royal Ontario Museum called Scopify uses your iPhone or Android smartphone to simulate thirteen different research tools, from CT Scans and UV lights, to microscopes and periscopes. Instead of simply taking a picture, you can now use your cameraphone to scan selected artifacts on display, CT scanning the mummies, for example, to see their bones wrapped within or spectral scanning diamonds to see the way they fluoresce under UV light.

Developed by Kensington Communications here in Canada, Scopify is a brilliant approach is it uses a different set of scopes from its virtual treasure box of lenses to tell each artifact’s story uniquely. You can add replica skin to dinosaur skeletons, restore Roman gladiator helmets, and use a periscope attachment to carefully peer inside a Minoan coffin without disturbing its contents. The results of each scan is saved to your phone so you can take it with you and study at home.

The popularity of cameraphones in public spaces make it clear that people want to see life through a lens and since so much of science research involves doing just that, institutions like the ROM are uniquely positioned to make that habit a rewarding one. The beauty of Scopify is that it can grow by adding new scopes and adapt to different museums or gallery spaces. It’s a tool, not a brochure, and so the potential is unlimited.

Long Distance Art

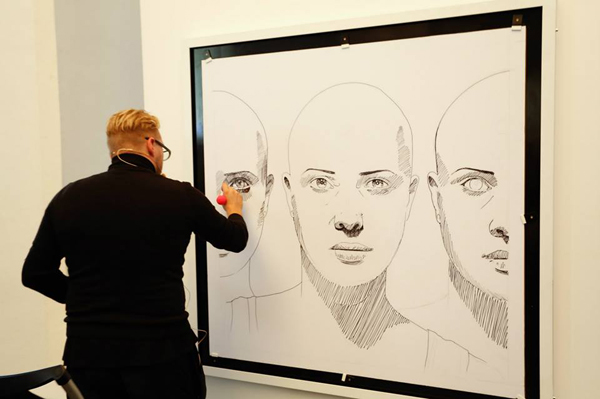

Have you ever wished you could be in three places at once? Up-and-coming artist Alex Kieslling managed to do just that for his latest art show by sending robots to London and Berlin to draw in his place while he worked on a canvas in a gallery in Vienna.

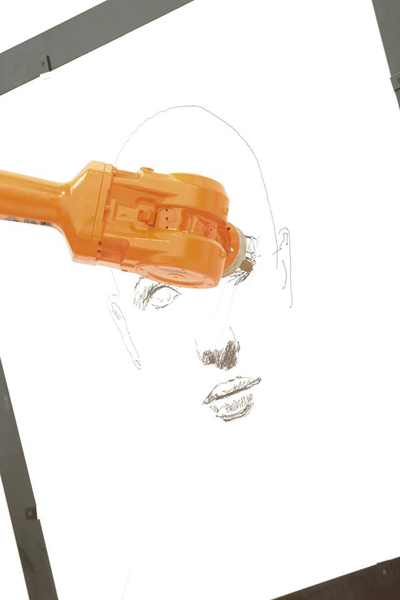

A computer system was used to track Kieslling as he drew through a system of infrared sensors and a Kinect camera system. Both the movements of his pen and his arms were captured and then sent through the internet to his robots, each an industrial arm like the kind used on assembly lines, who then duplicated his movements on their own matching canvases.

Visitors in any of the three cities could watch a streamed broadcast showing how all three drawings came into existence simultaneously and since Kieslling designed his illustration around connecting faces, the three finishes canvases were later connected as a triptych, creating faces that were half-drawn by him and half-drawn by the robots. Can you tell the difference?

For Kieslling the fascinating part of the experiment was in learning to change his drawing technique so that it could compliment the way the robots drew. In other words, it wasn’t just about transmitting hit art across cities, but in finding a way to work co-operatively with the robots too.